The Teachers We Didn't Expect

Life As We See It: On presence, grief, and the wisdom we almost missed

I’ve spent most of my corporate career “measuring” people.

Not literally, of course. But close enough. Over 10,000 interviews, several million survey responses, and over a thousand focus groups. I’m paid to understand human behavior, to predict what people would do based on who they are.

Education level. Income bracket. Job title. Psychometrics. I’d take IQ scores if I could get them.

I was good at it. Really good at it.

You’d be surprised at what I can predict about you based on a conversation. Psh, back in the day, I could probably name the brand of ketchup you buy.

I could tell within five minutes whether someone would give us “useful” data. I’d learned to spot “intelligence,” articulation, strategic thinking—all the markers our society uses to determine who has something worth hearing.

Then my brain broke.

Traumatic brain injury. Suddenly I was on the other side of those measurements. Watching medical professionals measure my worth through their tests and concerned faces.

I had been cruel.

All those interviews where I’d dismissed someone’s insight because they couldn’t articulate it the way I wanted. I’d built a career on sorting people into categories of value, never questioning whether the categories themselves diminished us all.

But that realization wasn’t enough to crack the framework. That came later, in a waiting room, watching a woman love her husband who couldn’t remember her name. Watching him teach me about presence, while every measure we use said he had nothing left to offer.

When Nancy reached out wanting to share what her daughter Sheila had taught her about living in the moment, I recognized something. That slow, uncomfortable realization that the person you thought needed your guidance has been teaching you all along.

This is Nancy’s story and mine. About recognizing the teachers who’ve been right in front of us.

Nancy...

Having a child with Down syndrome is an on-going lesson in adapting and changing. One of my earliest lessons came when Sheila was not yet 2 months old.

My husband and I attended a conference our local Down syndrome support group hosted. The keynote speaker was Emily Perl Kingsley. At that time, she was still writing for Sesame Street. She was also the mother of a son with Down syndrome (who was often one of the children on the show). She discussed the importance of taking one day at a time and not getting “too far ahead of yourselves.”

“Live in the moment,” was her rallying cry.

My arms tightened around Sheila, startling her awake. I forced myself to relax with a few deep breaths. Easier said than done, I thought.

Living in the present is much easier said than done, especially when you’ve just given birth to a child with a disability and there are so many unknowns.

When will she roll over? Or sit up, walk, talk?

When faced with unknowns it is so easy to perseverate on these endless loop questions. I became involved with the local support group and instigated restarting a playgroup for babies, toddlers and preschoolers. The good was the support it provided. The bad was the comparisons it inevitably created.

I found it easy to let go of comparing Sheila’s developmental progress with her sister’s. Where I struggled was at the support playgroup. Seeing other three-year-olds with Down syndrome beginning to talk while Sheila wasn’t even babbling left me feeling bereft. I longed to hear her talk.

I started working on taking deep breaths, then reminding myself of Kingsley’s rallying cry, “Live in the moment.” This became a signal to let go of the worry and stay present.

Two-steps forward, one-step back.

The pediatric nurse in me knew there would be help and support along the way. The mom part of me was terrified. What if Sheila never talked? What if I never heard her say, “I love you?”

What if I couldn’t give Sheila enough support and have anything left over for my other daughters? So much of my time was absorbed by Sheila, our middle child. I realized I had to become intentional about carving out individual one-on-one time with my other two girls and not feel guilty about it.

Learning to not feel guilty about taking time for myself also had to become a priority.

I started reading everything I could get my hands on related to the growth and development of a child with Down syndrome. I learned as much as I could about their learning style. They are primarily visual learners—they need models, visual aids, observation of what others do, and they are concrete thinkers.

Sheila fit the mold.

It also became clear that Sheila lived in the present. She didn’t spend time worrying about the future or dwelling about what happened in the past.

It is a lesson that I continually struggled with as she was growing up.

In this, Sheila became the teacher.

Alex...

Years later, I was the one sitting in a waiting room, supposedly there to get fixed.

Brain rehabilitation center. Every week, same uncomfortable chairs, same fluorescent lights humming their anxious song. I was there because a traumatic brain injury had shattered my ability to perform the version of myself I thought I needed to be.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. I’d spent years as a researcher studying human behavior, conducting thousands of interviews about authenticity. I could tell you exactly what the data said about presence and wholeness.

I just couldn’t inhabit any of it.

But there was this couple. Elderly. They sat in the same spot every week. He had severe dementia. She’d been his wife for fifty years.

I watched her meet him exactly where he was.

Sometimes he was lucid, telling stories about his days in the army with perfect clarity. Sometimes he was lost, confused about where he was or why. Sometimes he didn’t know her name.

She never flinched. Never corrected. Never tried to pull him back to some version of reality he couldn’t access.

She’d laugh sometimes, catching my eye. “The moments where I’m just a little frustrated? Well, he forgets. Good thing too, because they don’t happen often. After 50 years, he was so good to me. I want to be as good to him as I can be.”

I was a stranger to him every single week.

Every time we met, it was the first time. He’d light up, tell me about his fantastical adventures as a banker, these elaborate stories that may or may not have happened the way he remembered them. We’d be fully there together, completely present in whatever world he was inhabiting that day.

Then I’d stand up, walk through the door to my appointment, and the entire relationship would reset.

He’d never remember me. But I’d remember what I witnessed between them.

Nancy...

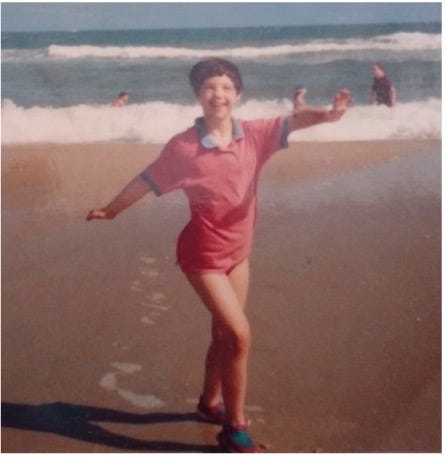

One moment, forever etched in my brain, is Sheila twirling and whirling along the edge of the ocean.

Sheila had a long verbal speech language delay. Despite her lack of speech, she communicated through gestures, rudimentary signs (signing exact English) and Sheila “made up” signs. Adding her signs along with observing her emotions via body language we began to realize, Sheila lives in the moment, all day, every day.

She embodied Kingsley’s rallying cry, “live in the moment.” Sheila’s emotions informed us she was not weighed down by grudges, nor were her moods governed by fears of the future. She just “was”—she was present in the moment.

It was the moment, by the sea, dancing in and out of the waves lapping the shore. I knew she was right there fully enjoying the pull of the waves, not worrying about the heat, or the kamikaze mosquitoes following the hurricane that had run up the coast the week before.

By contrast, the rest of us complained about the heat, humidity and the mosquitoes. It impacted our enjoyment of the moment while she danced by the sea running a low-grade temperature as her pituitary gland was failing.

The low-grade fever every day nagged at my pediatric nurse brain. She was susceptible to sinus infections, but there were no other symptoms. Worry about her health pulled me from maintaining a Zen, live-in-the-moment place. I constantly had this push-pull relationship between worry and trying to stay present.

But we were on vacation, at the ocean. Waves lapping on the shore, long walks on the beach helped convert worry to a more “be like Sheila” state.

Alex...

Here’s what I couldn’t stop thinking about: even when he struggled to remember her name, her face, their entire history together, he never forgot her presence.

Not her identity. Her presence.

The way his whole body would relax when she walked back from the front desk. How he’d reach for her hand without knowing why, just that it felt right. The softening in his face when she spoke, even when the words themselves made no sense to him.

She wasn’t trying to make him remember. She wasn’t performing some idealized version of caregiving for an audience. She was just meeting him, moment after moment, exactly as he was.

No agenda to fix. No need for him to be anyone other than who he was right then.

I realized I was watching something I’d been trying to intellectualize my way into for years. All that research about authenticity and presence, all those interviews about what makes people come alive, all that data about how we perform ourselves into exhaustion.

She was showing me what I’d been studying.

Presence isn’t a technique. It’s not something you achieve through practice or perfect through repetition.

It’s what emerges when you stop trying to make the moment into something other than what it already is.

Nancy’s story and mine keep circling back to the same uncomfortable truth: the people we think need our guidance are often the ones teaching us how to be alive.

Not because they’re inspiring despite their challenges. That’s the patronizing version we tell ourselves to feel better about our own discomfort.

Because they’ve learned to inhabit reality without the crushing weight of pretending it’s something else.

Sheila dancing by the ocean with a fever. Not performing joy. Just being joyful.

The man with dementia reaching for his wife’s hand. Not remembering their story. Just knowing her presence.

Both of them showing us what presence actually looks like when we stop making it complicated.

Our culture is obsessed with optimization. With improvement. With fixing what’s “broken” and enhancing what’s “normal.” We measure intelligence, track development, compare milestones.

We create elaborate systems to determine who has value and who needs help.

I say this as someone who spent years believing my worth was tied to my cognitive performance. Who thought the brain injury made me less than. Who’s still fighting the impulse sometimes to prove I’m “better” now.

Nancy learned this with Sheila. I discovered it in that waiting room.

The wisdom we’re looking for isn’t hiding in the places our culture tells us to search.

It’s dancing by the ocean. It’s sitting in waiting room chairs. It’s in the people we thought needed us, patiently showing us what we forgot.

They were never the students.

We were.

Nancy...

Sheila died two years ago. Her death unleashed a grief more intense than I have ever experienced before.

When I was a young girl, I learned to stuff all my feelings down. It took several years of counseling to start recognizing and honoring my feelings.

Then Sheila came along and every feeling she had was right there, in the moment. If it was joy she felt, we all saw it. If it was sadness, hurt or pain, it was right there.

None lasted forever. Each lasted as long as her “presence in the present” lasted.

With her death, my ever-present teacher, my role model of living in the moment, is gone.

Grief gave me an opportunity to embrace what I was feeling, acknowledging each feeling throughout the day. Yes, the first days, weeks, months meant there were more tears than I had cried in all the prior years of my life.

At the same time, I understood that honoring, accepting and leaning into each feeling would help me move forward.

I cannot think of a better way to honor the importance of Sheila’s life than by being intentional about staying present in each moment of the rest of my life.

This might matter to someone you know who’s measuring worth in all the wrong ways. Would you share it with them?

About Nancy

I’m Nancy Holroyd – pediatric and school nurse, mother, disability advocate, and writer.

Nurse for over 50 years (mostly retired, but not completely), mother for 40 years. Gave birth to three girls. Survived the excruciatingly painful death of our middle daughter who taught her whole family about unconditional love.

Writing started as a means of coping with the birth of a child with a disability. Now I write about raising, loving, saying goodbye, and grief.

I, also, write about topics adjacent to school nurses, school nursing and parenting.

About Alex

I’m Alex Lovell — political psychologist, yoga therapist, and writer.

Lived homeless. Been divorced. Survived a seven-car pileup with a semi. Fell in love with questions that don’t have easy answers. I’ve met a lot of thresholds. Even the one before death.

These days, I split my time between research, writing, and holding space for people figuring out who they are after everything shifted.

This Substack is where I make sense of things out loud.

I write for people in transition — between roles, beliefs, relationships, selves.

The ones quietly wondering, “What now?” but allergic to one-size-fits-all answers.

Sometimes I quote research. Sometimes I quote my own nervous system.

One speaks in data, the other in sensation. I’ve stopped choosing sides.

Free subscribers get weekly articles and insights (sometimes twice a week!). Paid subscribers get the Thursday Offerings, seasonal companion pages, post-nidra audio, and live slow sessions. Join me?

Erin, thank you! 💙💛💙

Thank you for sharing this beautiful post. Everything shifted for me when my daughter Aix was diagnosed with bipolar disorder her freshman year of college and when she died at age twenty-five. I’ve had to learn to shift my expectations and to live in the moment. Your stories resonated with me.